[This blog was originally published in Night Owl Reviews]

Crack open any Storytelling 101 book and it’ll tell you conflict is your story’s engine. Every story since the history of forever has centered around someone trying to solve a problem; otherwise, it’s not a story so much as a series of anecdotes, or an aside, or your drunk uncle’s ramblings.

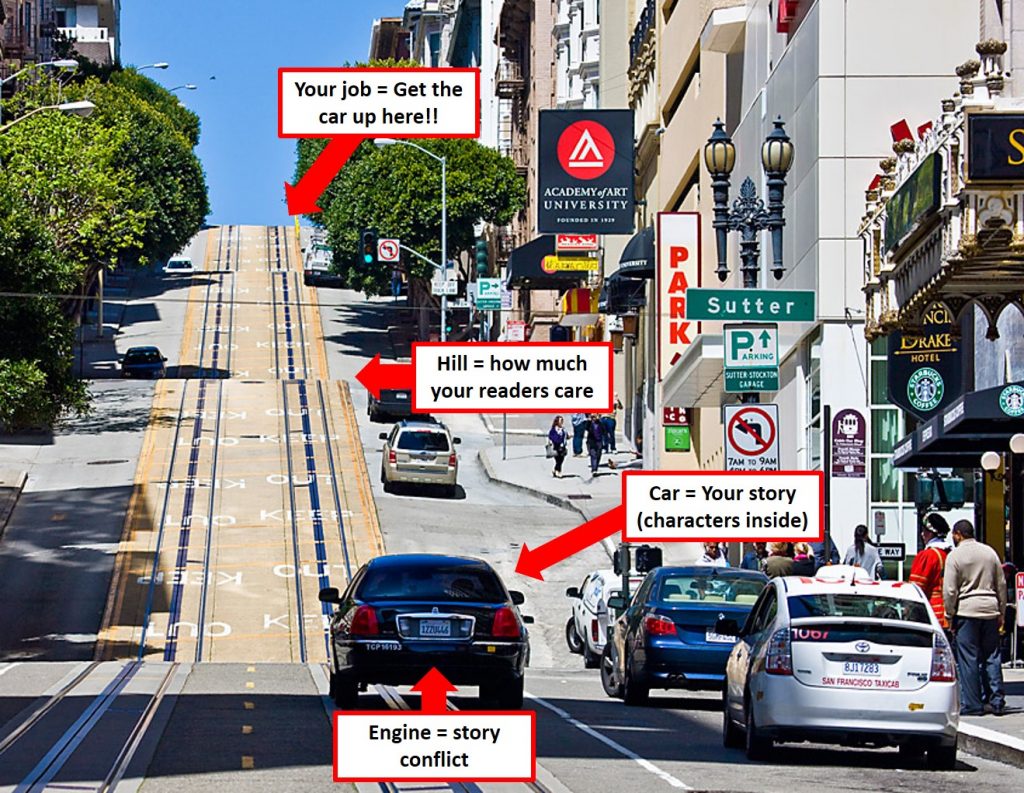

Stories which lack a strong central conflict feel weak or meandering. They “peter out,” we say, like a Toyota Camry with a 4-cylinder engine trying to lug you and your 250-pound friend Denny up one of those iconic San Francisco cityscape hills as cars honk behind you. No offense to Denny—he’s an awesome guy—or Camrys or San Francisco. The point is your conflict—specifically, what’s keeping your protagonist from getting what they want—needs to propel the entire story. If it’s not strong enough, then even the flashiest car (i.e. your concept) packed with the best people (i.e. your characters) still won’t be able to get up that hill (i.e. reader engagement).

There are lots of ways to create conflict, but the most tried-and-true method is through a villain. A villain’s purpose is to antagonize the protagonist and keep your hero from getting what they want. Villains are staples of fiction because they focus the audience’s attention, giving us something to root against while rooting for the hero.

[One important detail here – a villain is a specific kind of antagonist. An antagonist is any force, usually a person, preventing the protagonist from getting what they want and/or need. An antagonist isn’t necessarily a bad person – for instance, in romantic comedies the central pair are often each other’s antagonists (sparks fly!). A villain is a specific kind of antagonist who has malicious intent.]

The best villains are captivating and commanding, often more so than the hero. Honestly, most heroes are boring on their own. Who gives a crap about Ned Stark if Joffrey isn’t turning his screws? Who would Batman be if he had no one to fight…does anybody really care about Bruce Wayne? (Answer: no) Would Luke Skywalker have ever left Tatooine if Darth Vader’s henchmen hadn’t offed his adoptive parents?

But despite a rogue’s gallery of classic villains to model from, writers screw them up all the time. Why do the vast majority of superhero villains feel so lame? Because many writers don’t understand the key components of a compelling villain. It’s not enough to say, “This person is EEEVILLLL!” and expect people to care. No toy company has ever sold a “generic forces of darkness” action figure.

If your villain is your primary engine of conflict, then you need to design that engine to match your car and the people you’ll be shuttling around. So here are the critical elements of a compelling villain:

- The villain should be the protagonist’s equal and opposite.

A good villain exploits the hero’s weaknesses and nullifies the hero’s strengths. Going with the Game of Thrones example: in the show’s first season/first book, Ned is the hero while Joffrey is the (primary) villain. Ned is loyal, honest, and honorable. Joffrey is a back-stabbing, conniving liar. Ned has truth and justice on his side, but Joffrey has the absolute power of the king. Most of their fighting result in a stalemate…until the end, when we find out definitively which force is stronger. Joffrey is fascinating because he’s nearly the exact opposite of Ned, and Ned would be a pretty boring guy to follow if he weren’t constantly clashing with Joffrey.

- The villain and the protagonist should want the same thing.

It’s not enough for your villain to be a jerk solely for the joy of it. That’s why “ancient evil that wants to destroy and/or take over the world” narratives usually aren’t very interesting. It’s not specific enough. When the villain and hero want the same thing, we can focus directly on their struggle—with the realization that only one of them can win. It ups the stakes. In Game of Thrones, Ned and Joffrey both want control of the Iron Throne. Ned doesn’t want to be king, but he doesn’t want Joffrey to shatter the fragile peace Robert had established. Therefore, Ned wants to set limits on the king’s powers. Joffrey, of course, wants no limits. The personal stakes couldn’t be higher for both of them, and that’s what makes their conflict compelling.

- The villain should be capable of succeeding.

This is a big one which many writers often bungle. In order to set the hero up for success, villains are talked up but neutered into incompetence (all bark, no bite), or given goals they have no hope of achieving, like taking over and/or destroying the world (OF COURSE that’s not gonna happen, come on people). If you know off the bat the heroes will prevail without much of a problem, then all you’ve signed up for is to witness a slugfest (which is why I don’t watch most superhero movies—they’re boring). The audience knows nearly every fictional story is committed to a happy ending, but a writer needs to at least make it seem like the villain has a real chance at success. In Game of Thrones, Joffrey does in fact succeed in a spectacular show of force—but it’s short-lived. The happy ending—if there is one—will come after many, many villain successes…which will make the hero’s journey (not Ned’s ☹) all the more sweeter.