[This article first appeared in Night Owl Reviews]

I used to wonder what was more important—wordsmithing or storytelling. This was when I was on my O. Henry Prize kick, reading dozens of beautifully written short stories that received high praise despite lacking plots or any deep meaning (to me, anyway). As a result, for a while I believed wordsmithing was more important and focused a lot on improving my prose. Then I realized short stories were a career dead end and began focusing on novels, where I came to the opposite conclusion, and the one I believe today: ideally you want to be good at both wordsmithing and storytelling, but storytelling should always take precedence. Beautifully constructed sentences and imagery are great and all, but if they don’t coalesce into anything meaningful it becomes tiresome after a while, like the O. Henry stories did for me; it’s the literary equivalent of navel-gazing.

In the end, words are tools you use to tell your story.

For a novelist, they’re your primary medium, like paint to a painter. The individual brushstrokes aren’t nearly as important as the completed composition. As such, grammar is important, but if that’s your primary focus then you’re doing it wrong.

On that note, here’s a quick list of the biggest supposed grammar no-nos people spend way too much time obsessing over instead of improving their storytelling craft.

1. Who vs Whom

Supposedly you should use “whom” when referring to the object of a preposition or verb. This is one of those rules grammar snobs LOVE to correct people on—because that’s how you know they’re smart (otherwise, how would you know?)! However, the use of whom has fallen out of favor over the last few years, with most pro novelists opting to simply use “who” in all circumstances since both words are functionally the same. And thank you Jesus for that! Having to stop writing and think hard about whether to use who or whom when there’s no real difference between them is a waste of valuable brain resources.

2. Passive Voice

Passive voice is putting the subject before the verb, ala “Bob was punched by Jeff” instead of “Jeff punched Bob.” Good writing maximizes economy, saying the most with as few words as possible. Passive voice violates this rule and is therefore looked down upon. It’s also one of the easiest rules to understand, so the mostly-grammar illiterate will latch onto it to an obnoxious degree. There are, though, several reasons you may want to use the passive voice. For instance, if the subject is more important than the object, i.e. “President Shot by Assassin!” or if you want to be intentionally vague about the object of the sentence, i.e. “I’m sorry, ma’am, your husband was killed last night.”

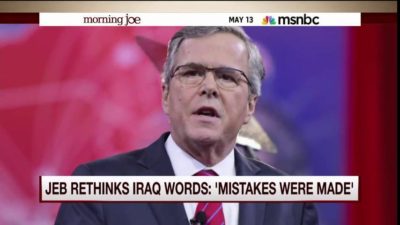

My favorite example of intentional passive voice: “Mistakes were made.”

Really? By who? I wonder why he isn’t being specific.

3. Never use “very” or “suddenly”

An author in my writing group told me they had an English instructor once who said any assignment with the words “very” or “suddenly” was an automatic fail, to which I rolled my eyes so hard they got stuck in the back of my head for a moment. It’s true bad writers can abuse these words to create flat prose, but banning words doesn’t make someone a good writer, either. Good writers can use these verboten words to great effect; for instance:

Sentence 1: “He was tall and black.”

Sentence 2: “He was tall and very black.”

Notice how the addition of one word adds another layer of meaning to the sentence? That’s good writing, no matter what any English professor tells you.

4. Kill your adverbs

Yes, it’s good to avoid adverbs. No, this doesn’t mean you should forsake all adverbs. Remember, good writing prioritizes the economy of words. The reason this sentence: “‘I’m sorry,’ John said sadly” is inferior to this sentence: “‘I’m sorry,’ John said, tears rolling down his cheeks,” is because the second sentence gives us a vivid mental picture and therefore relays more information than the ambiguous adverb “sadly.” However, some adverbs are vivid enough to stand alone. For example: “‘I remember that,” she said whimsically.” Whimsy is a pretty specific emotion; no need to elaborate. Conversely, sometimes you don’t need to be specific: “John rose slowly.” Unless there’s something special about the way John slowly rose, there’s no need to punch it up with an exciting verb or extra description.

And there you have it. The point is this: if your prose says what you want it to say in as few words as possible, then go for it, grammar “rules” be damned.